In the bar industry, mezcal is big, but still so little is known about this artisanal spirit. Tom Bartram takes you through the rudiments of a diverse and sometimes confusing category.

Photography: Anna Bruce

Once dismissed as a smoky curiosity, barely known outside rural Mexico, mezcal’s dramatic rise was an unexpected development of the last decade. Between 2011 and 2018, certified annual mezcal production

grew fivefold from 0.9 million litres to 5.1 million. At first glance the spirit can appear unrefined and fierce, but on further inspection there’s an incredible level of sophistication and complexity, and a rustic charm that’s amassed fervent devotees across the globe. With the UK being the fourth largest export market after the US, Spain and France, it may be time to ask yourself if you really know Mexico’s ancestral spirit?

Historians will tell you mezcal is North America’s oldest spirit, first recorded in 1619. In Mexico’s ancient Nahuatl language, metl-ixcalli means cooked agave. Hispanicised to mezcal, it became the term for all agave spirits produced across the country. It’s said “all tequila is mezcal, but not all mezcal is tequila”.

However, Mexican law will tell you since the creation of the Mezcal Denomination of Origin in 1994, mezcal is its own specific category, separate to the other agave spirit denominations of tequila, bacanora, raicilla, and sotol (sotol is not technically agave, but it’s usually lumped in).

But to understand the true soul of mezcal, you need to ask the people who make it. They will tell you that mezcal is a way of life. At every wedding, christening, funeral and fiesta, you will find mezcal. “Para todo mal, mezcal, para todo bien, tambien” – for all evil, mezcal, for all good, too.

Like tequila, mezcal is made from agave, a succulent native to the Americas, often called maguey (pronounced ma-GAY). Unlike tequila, by law all exported mezcal is 100% agave and, whereas tequila is limited to agave tequilana weber var.azul (aka blue agave), mezcal can use any of the numerous species. Each gives distinct aromatic profiles, and there are more distinct varieties of agave used for mezcal than varieties of plant used for any other spirit.

In addition to their botanical names, each agave has local names, which can vary from village to village where numerous indigenous languages are spoken. For example, agave angustifolia is most known by the local name espadin, so called as its leaves resemble a sword of the same name, but in other parts it’s known as espadilla, or doba-yej.

To get acquainted, start with espadin, the most widely used, accounting for more than 75% of mezcal production. Not as distinct in flavour as others, it shows its environment and the hand of the producer. Next up: tobala – a small variety growing from the crags of mountains, with complex, often mineral and earthy aromas; cupreata – the dominant variety in the states of Guerrero and Michoacan, with a creamy, fruity profile; kawinskii – a tall, tree-like species with lots of subspecies, eg tobaziche, cuishe, madrecuixe, barril etc, often having sweet herbal notes; tepextate – up to 30 years to mature, it makes a complex floral, herbal mezcal, sometimes with notes of nori.

Regional variation

Blends of different agaves, called ensembles, are also widely available. In no way inferior to single agave mezcals, they represent an old style of mezcal made from whatever agave were mature at the time.

Another difference to tequila is the region. The mezcal denomination covers more than 500,000km2, larger than any other protected spirits region, 500 times that of Cognac, seven times the size of Scotland. Incorporating arid valleys, high-altitude pine forests, grass-filled pastures, and everything in between, it spans nine states: Oaxaca, Guerrero, Puebla, Michoacan, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosi, Zacatecas, Durango, and Tamaulipas. Bearing in mind agave’s lengthy maturation, absorbing characteristics from the ground, air and surrounding flora, the regional variation that mezcal can express is off the charts.

More than 92% of mezcal is made in Oaxaca (pronounced wa-HA-ca). Positioned at the diversion of two major mountain ranges, it’s Mexico’s most geographically diverse state, containing more agave species than any other. The style of mezcal varies from village to village, and it’s best to explore through tasting. But be sure not to miss the other states within the denomination, which have their own unique agaves and terroir.

It is difficult to describe the production of such a spirit without employing overused descriptors such as craft, artisanal and handmade, but mezcal truly embodies these notions. Typical small-scale mezcal production takes place in Palenques (aka Tabernas or Vinatas in other parts); agaves are typically cooked in earthen pit ovens that give many mezcals their distinctive smokiness. The type of wood, arrangement of the pit and cooking time (typically three to five days) will affect the profile. After crushing to extract the sweet juice, all-natural open vat fermentation adds to the spirit’s complexity and uniqueness as ambient yeast vary from producer to producer. The spirit is distilled in anything from a more conventional copper pot still to one made of clay or wood, and many mezcaleros choose not to add any water to their spirit after distillation. “Mezcal con agua no es mezcal.” (Mezcal with water is not mezcal.)

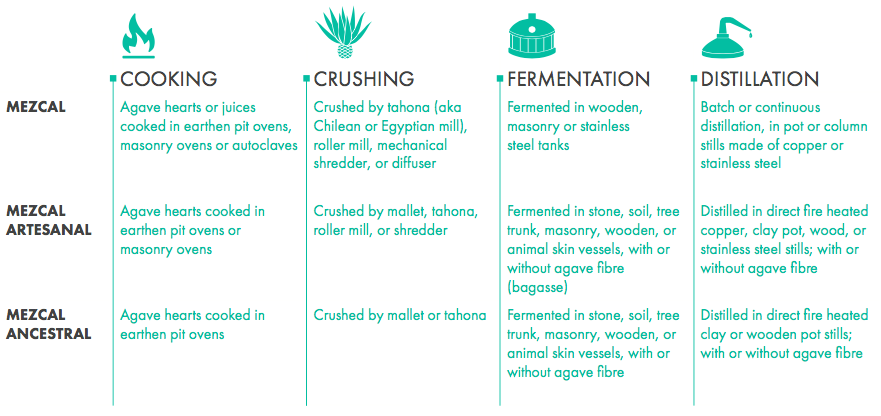

To illustrate in numbers, mezcal’s circa 1,800 certified producers make as much spirit as just two average tequila distilleries. No wonder the category employs more people per bottle than any other widely distributed spirit, in part explaining the relatively high prices. Traditional production is highly valued but, with the category’s success, more industrial distilleries are popping up. So, in 2016 regulations were updated to protect artisanal and ancestral methods, introducing the following categories: Mezcal – the most industrial style using modern means of production, resembling large tequila producers; Mezcal Artisanal – typical small and medium size producers, accounting for 92% of mezcal; Mezcal Ancestral – reserved for the most ancient techniques, making up just 1% of production. See table for full production requirements.

Other labelling terms are: Joven (young, pronounced HOH-ben) – unaged mezcal, accounting for 98% of production, as many feel oak ageing is detrimental to mezcal’s complex flavour; Reposado (rested) and Anejo (aged) – like tequila aged a minimum of two and 12 months respectively in wood; Madurado en Vidrio (matured in glass at least 5l capacity for a minimum of 12 months) – makes a surprising impact on the integration of flavour and texture; Abocado con (flavoured with) – fruits, coffee, or the infamous gusano worm, which frequents industrial mezcals; Destilado con (distilled with) –including pechuga, a culturally significant, often pricey mezcal redistilled with chicken or turkey breast suspended in the still with seasonal fruits and nuts.

As to how to drink mezcal? Traditionally always neat, perhaps alongside food, or a wedge of orange covered in sal de gusano (worm salt). In cocktails, it can be used as a base spirit in more flavourful cocktails, or more subtly as a modifier, or even as a spray to garnish. Many classic cocktails can be given a mezcal twist. Try swapping out the gin in a Negroni, the tequila in a Tommy's Margarita or Toreador, or add a dash into a Tequila Old Fashioned to make Death & Co’s neoclassic Oaxaca Old Fashioned.