As a category dominated by big brands, does cognac exhibit that oh-so French term ‘terroir’? Edward Bates digs deep for the answers.

Cognac. A drink, a place, a word, recognised from Solihull to Shanghai, from Margate to Mumbai, as the very quintessence of all things sophisticated and French. So everyone around the world knows and understands cognac, right?

Not quite. Let’s look at a few numbers. Around 17.6m 9-litre cases of cognac are sold each year and of those almost 98% are exported – QED, the French don’t drink cognac. Around 90% of sales are by the big four houses – Hennessy, Martell, Courvoisier and Rémy Martin. Hennessy accounts for around 50% of the market as a whole.

So, the world thinks that cognac tastes like Hennessy. If so, the world is mistaken. Don’t get me wrong, Hennessy makes some quite wonderful things, but there are around 300 other producers. Do they offer something different? They have to.

Let’s start with some basics. What and where is Cognac? Apart from the town, Cognac is a region of western France, which covers more than 75,000ha around the River Charente with its maritime climate of warm summers and mild winters.

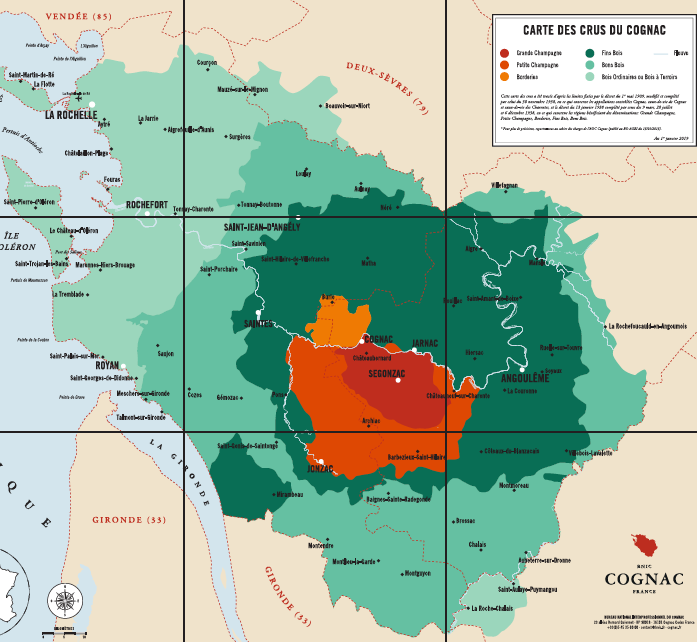

Its vineyards are divided into six sub-regions: Grande Champagne, Petite Champagne, Borderies, Fin Bois, Bon Bois and Bois Ordinaires. These are differentiated by the composition of the soils. In the middle of the region, Grande Champagne is dominated by chalk. In Bois Ordinaires there are vineyards planted on beaches, so sand is rather prevalent.

So, if the soil is different, the grapes should taste different and if the grapes taste different, the wine tastes different, correct? To try to explain, let’s look at a couple of smaller producers you may have heard of, in the case of Frapin, and may not have in Château de Beaulon. They have a few things in common. Both are family owned, Frapin started growing vines in 1270, with Château de Beaulon being a relative newcomer, starting in 1712, with the château itself dating from 1480. The château is something else the two properties have in common. Frapin’s main estate is at Château Fontpinot, home to its eponymous range of cognacs – any cognac with the name of a château on it means that the whole process of grape growing, wine making, distillation and maturation has to take place at the château.

So the cognacs of both houses are all about where they are from and who made them; the very essence of terroir. Terroir, one of those magnificent French words, which have no real English equivalent, can be defined as: the complete natural environment in which a particular wine is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography and climate. So, change the location, change the soil, climate etc, change of terroir. Change the terroir, change the cognac.

A look at Cognac

Time to look at a map. The BNIC publishes a map of the six sub-regions of Cognac. Right in the middle is Grande Champagne. Soft, rolling hills with chalk soils. Imagine the South Downs, just with a few more vines. Right in the middle is the sleepy, one-bar village of Segonzac. About 6km outside Segonzac, just off the D736, is Château Fontpinot.

Going back to the map, towards the bottom there is the mouth of the Gironde. The northern banks of the river here have light, sandy soils. Surrounded by the region of Bon Bois is a small outcrop of Fin Bois and the small town of Saint-Dizant-du-Gua, home of Château de Beaulon. Two châteaux, two locations, two soil types. But there is much more to terroir than just soil. Cognac is made from wine, for which you need grapes. Do the grapes make a difference? Yes.

In common with more than 95% of cognac produced, Frapin uses Ugni Blanc for its cognacs. In the 19th century most cognac houses used Folle Blanche, then between around 1863 and 1890 phylloxera wiped out some 75% of French wine grapes. When Cognac growers replanted they almost universally chose Ugni Blanc, because of its disease resistance. Château de Beaulon, however, chooses to do things differently. Remember its location – those sea breezes coming off Gironde mean that mildew, to which Folle Balance is particularly susceptible, isn’t such an issue. So it chooses to use three traditional varieties – Colombard, Montils and Folle Blanche. No Ugni Blanc at all.

Soil types, locations and grape varieties – so that’s terroir? Not quite. Remember we’re dealing with wood-matured wine distillate. The distillation itself is not really a variable. All producers have to use small – 2,500-litre – pot stills, the size and design of which don’t change much from producer to producer. The warehouse and cellars, however, vary greatly. Just as in Kentucky, each cellarmaster understands how cask location and relative humidity level changes the flavours in the cask drastically. Typically each property will have a dry cellar and a humid cellar. Dry cellars give big, powerful, full-flavoured cognacs, with humid cellars producing spirit that is lighter and more delicate. However, given the differences in location, as with Frapin and De Beaulon, one property’s dry cellar may well be more humid than another’s humid cellar.

Here you also introduce the final and, in my opinion, most important variable in the concept of terroir – the cellarmasters themselves who, because of the decisions they make, fundamentally affect the flavours in your glass.

All well and good, but what does this all mean in the glass itself ? OK, let’s go back to our friends at Frapin and De Beaulon. Frapin’s cognacs are typical of Grande Champagne cognac – its Château Fontpinot XO is one of my favourites, aged for more than 20 years in dry cellars, giving candied fruit aromas, marzipan, hazelnut and nougat. Balanced, rich and complex on the palate. Contrast that with Château de Beaulon’s XO, which overall has much more floral notes with fresh wild peach. The fruitiness comes through on the palate, which is delightfully fresh and vibrant. Totally different. Think Ardbeg and Auchentoshan; Chablis and Claret – that’s how different.

So, is terroir a thing in Cognac? In the small houses, absolutely.