It’s been six long months since we last saw bars open indoors in England. Hamish Smith looks back – and forward.

The rhetoric was that the timeline of reopening society and businesses in England was driven by data over dates. Yet, here we are in May, having reopened hospitality indoors and out on the very dates set out in February.

That’s either extraordinarily good guesswork, or evidence that dates did indeed trump data. When Boris Johnston said the roadmap was irreversible, it turns out he was right. Just not in the way we might have expected.

Since the retreat of the winter wave, Covid rates have bettered our scientists’ best-case scenarios. All the while hospitality lost £200m every day it was shuttered, with businesses perishing all around us. Every day counted.

But now we are here, somewhat ambivalently there is also a sense of relief. Given the terrain when the roadmap was laid out – and not least the navigator – diversions, if not calamity, seemed inevitable.

We have come so far, but we have learned little definitively about the transmissibility of a virus that has wreaked such havoc on hospitality. The latest SAGE Report, published in late April, drew mixed, if not conflicting, conclusions about the risk of visiting pubs and bars. One case-control study noted “going to a pub or bar was associated with increased odds of [contracting coronavirus],” another reported “some weak evidence” to this, and a third case-control study found “no evidence that going to pubs and bars was associated with increased odds of becoming a Covid-19 case”.

These studies follow a pattern of uncertain science. The Public Health England Covid incident statistics that were billboarded on social media throughout the past year – normally to the effect that hospitality made up 1-5% of Covid cases – engendered an understandable feeling of victimisation across the industry, when really, they were next to meaningless.

As a spokesperson from PHE told Class last year, cases in transient spaces such as hospitality aren’t investigated unless there are significant outbreaks. To this day, no one has clear data on the risk of transmission in hospitality – not SAGE, PHE, not Test & Trace, which barely used check-in data – and certainly not the government.

No, for much of last year the government seemed to have been creating policy based on even sketchier insight – that people testing positive for Covid were likely to have recently visited hospitality venues, which presumably they could have arrived at via public transport, possibly after work, during which they might have bought their lunch in a supermarket. The evidence for the basis of the curfew has never been found – indeed, even according to one SAGE admission, it never existed.

Argument dismissed

It is against this backdrop Punch Taverns founder Hugh Osmond and Sacha Lord, the night-time economy adviser for Greater Manchester, took the government to court last month. Their argument, that there is no evidence that hospitality caries a heightened risk of Covid over other public indoor spaces, was dismissed as “academic”. The government stalled for time, ultimately killing the case. The aforementioned SAGE report was released shortly after the case was closed. Politics is a fine art.

If there is a broader church of consensus, it is that outdoor spaces carry very little risk of infection. This was confirmed recently when multiple studies showed that transmission is almost 20 times more likely inside than out. This has long been a First Principle of our understanding of the science of Covid transmission yet it was not acted on by the government. The unlocking of our outdoor social lives in April – and at other points over the pandemic – proved not to complicate the virus’ retreat, but has seen our streets lined with terraces, bringing life, joy and trade to our villages, towns and cities.

To think how many hospitality businesses might have been saved had they been able to claim the streets as their own over the past 15 months.

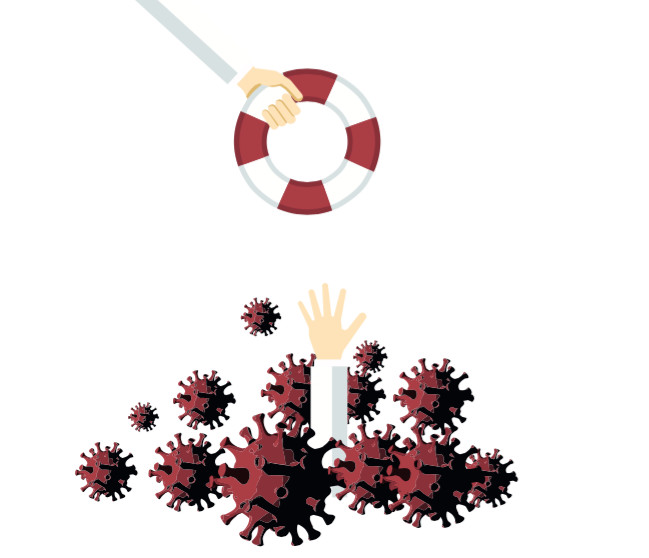

How surviving businesses have made it this far is between them, their gods and accountants, but perhaps now it is time to look forward, to archive our war stories for the grandchildren. The immediate reward is a public with a pent-up, and hopefully lasting, thirst for hospitality experiences. Custom is the cavalry on the hill after a bloody battle and if April’s outdoor trading performance is anything to go by, this spring and summer could be just as epic.

Looking beyond this spring and summer, while there is confidence and liquidity flowing through the veins of industry again, further obstacles surely await. Where pockets of the virus persist due to low vaccine take-up, local restrictions could still resurface. There too is the prospect of a Covid variant circumventing our vaccine defences.

With boosters announced to arrive by autumn, it feels like we are now playing an indefinite game of cat and mouse, but for once, there is a sense we are now the predator, not the prey. Indeed, that our leader is alleged to prefer even the most morbid outcome over further lockdowns, is probably the most persuasive indication that the roadmap won’t see a three-point turn.

Could we see vaccine passports? While playing a role in travel, it seems wholly unworkable at home, even less so in hospitality. The desired outcome – the certainty of safe spaces – would in practice be ethically and operationally problematic. Testing, as recent pilot events would suggest, seems a far likelier route, though the onus should fall on the customer – not, as some have suggested, hospitality staff. From a business perspective, such involved safety procedures seem unlikely to attract more people to our venues than their absence would deter.

What we all want is an uncomplicated night out, where we don’t necessarily have to book ahead to buy a drink, have our socialising reduced to a slot, scan and be scanned at the door. Optimistic perhaps, but normality is much closer now than in any time in the pandemic past.