Anastatia Miller & Jared Brown have discovered the true history of gin. Here they give us the headlines from their newly published A Most Noble Water: Revisiting the Origins of English Gin.

We love Martinis, and we love gin. We accidentally wrote our first drink book in 1996 – Shaken Not Stirred: A Celebration of the Martini – when we created a Martini website just to see if we could build a website, and a publisher asked to turn it into a book.

So it was about time we wrote about the history of English gin. Writing took a while. About three years. You know we love to dig deep and, without question, A Most Noble Water: Revisiting the Origins of English Gin contains the most momentous discoveries of our careers writing drink history.

We went through more than a few rounds at the National Archives, Wellcome Collection, British Library, Bodelian Library and an insane number of academic and vintage newspaper articles. What we found can be summed up in a single sentence: gin was not born in 17th-century Holland and imported to England.

Yeah, we know the tale about English soldiers getting their first taste of and for ‘Dutch courage’ during the Thirty Years War (1619-1649). Pretty hard to prove since the most popular local drink at the time was wormwood-infused wine. Even English writer Daniel Defoe’s claim that English troops in the Anglo-Dutch war (1652-1654) got a taste for spirits has been muddled by time. Truth is, Defoe wrote that the troops were introduced to brandy – not genever.

Professor Franciscus Sylvius dele Böe? He’s no longer part of the story. Eight years before Professor Sylvius was born in 1614 the Dutch States General had issued an ordinance in 1606 that taxed “all distilled wine, anise, genever, and fennel water” that was sold as social beverages instead of medicine. Although there are claims that the Bols Distillery first commercially produced and exported genever on a small scale in 1575 to England, it still gets trumped by the appearance of a German recipe for juniper berry distillate that was first published in a 1500 book which was translated and published in English in London in 1527.

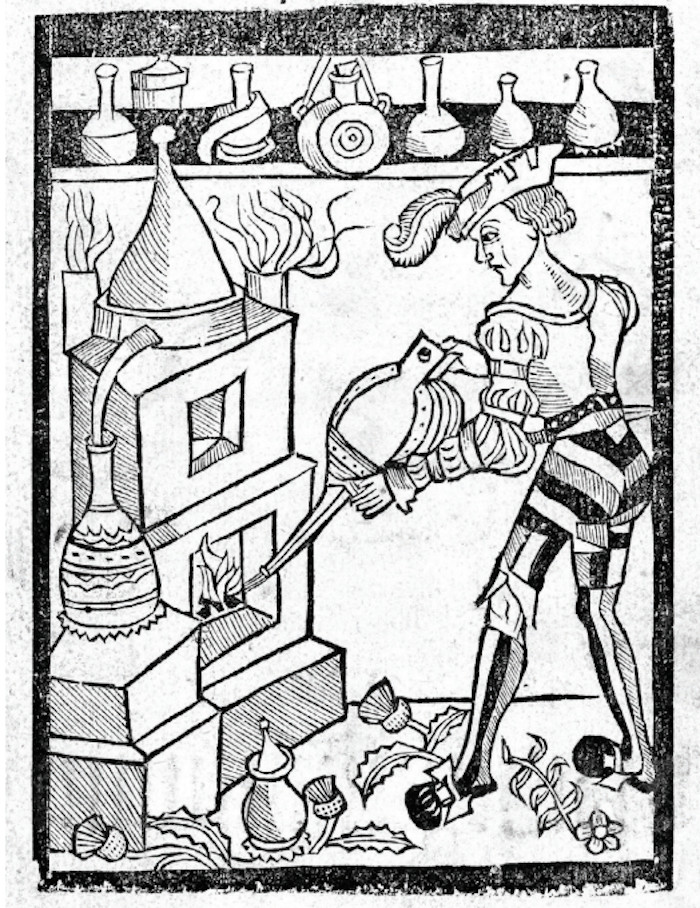

That’s right, in the mid-1400s German brandy distillers produced a juniper berry rectified brandy called walcholderbeerwasser. At the same time, German housewives took their leftover beer and distilled it on their stovetop stills with juniper berries to make cramatbeerwasser. The government tried to curb the production and sale of the latter, but you can’t keep an ambitious housewife-cum-brewer from making a bit of pocket money.

Getting back to England and the first translation of a German juniper distillate. We owe thanks to Johannes Gutenberg for his printing press invention which put thousands of copies of distillation books into the hands of apothecaries and literate women – the unsung heroines of medieval and early modern medical practice who could read and afford a ‘stillatory’ – or cold still. We must thank King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I for switching from wine to spirits such as aqua vitæ and aqua rosa solis in the late 1500s. We raise a toast to King James and his wife Queen Anne of Denmark for not only introducing spirits drinking to the royal court, but for granting charters to the growing number of apothecaries and distillers who produced medical and social spirits.

Standardised recipes

We thank the Worshipful Company of Distillers of London for standardising the recipes in 1639 for 34 distillates and 16 variations that their 100-plus membership produced in the city of London, including one that most closely resembled what became known as English gin – 50 years before the wormwood wine-loving William of Orange and Queen Mary took the English throne. Yes, there were over 1,500 distillers in London in those days with only 200-plus being monitored by the guild by the 1700s. Unlicensed distillers did produce their spirits with vitriol, turpentine, even ‘molasses’ spirit produced in Bristol.

Theirs was the ‘gin’ of the so-called Gin Craze. These dodgy spirits quickly disappeared, thanks in part to better distillation regulations by Parliament. It was a guild formula that evolved into the gin produced by the ‘gentlemen’ distillers of the 19th century, which is what we still consume in one style or another today.

For this evolution, we commend the pioneering inventors of the improved hydrometer and continuous column still for making pure grain spirit possible in quantities far greater than was possible during the previous centuries of English distillation. (That’s right. Even Geoffrey Chaucer used the word ‘stillatory’ in his 14th-century epic The Canterbury Tales.) What also made gin great by the mid-19th century was the fact that styles of gin became available that appealed to every taste and budget in the same way beer and ale styles varied throughout the UK. We are just beginning to see that depth and breadth of style emerging once again to a new audience of gin lovers.

So, now that we have explained what the story of gin isn’t, you might be wondering what exactly the origin story of gin is. Juniper distillates that eventually reached Britain originated in Austria and Germany. They arrived in the 1500s. By the 1630s, a uniquely English formula emerged which included juniper, citrus peels and spices, and was rectified or compounded rather than adding the botanicals into the first distillation. While dodgy rectifiers and spirits sellers produced cheap imitations, real English gin was born. From that time on, gin only evolved with advances in distilling technology and as regional variations gave birth to multiple gin styles.

A Most Noble Water: Revisiting the Origins of English Gin is available from mixellany.com and available from Amazon and other book sites.